The Kinnaird Ravine (Rat Creek) Bridge

82nd Street between 111th & 112th Avenues

Engineers: A.W. Haddow & R.J. Gibb of the City Engineering Dept.

Constructed: 1931-32

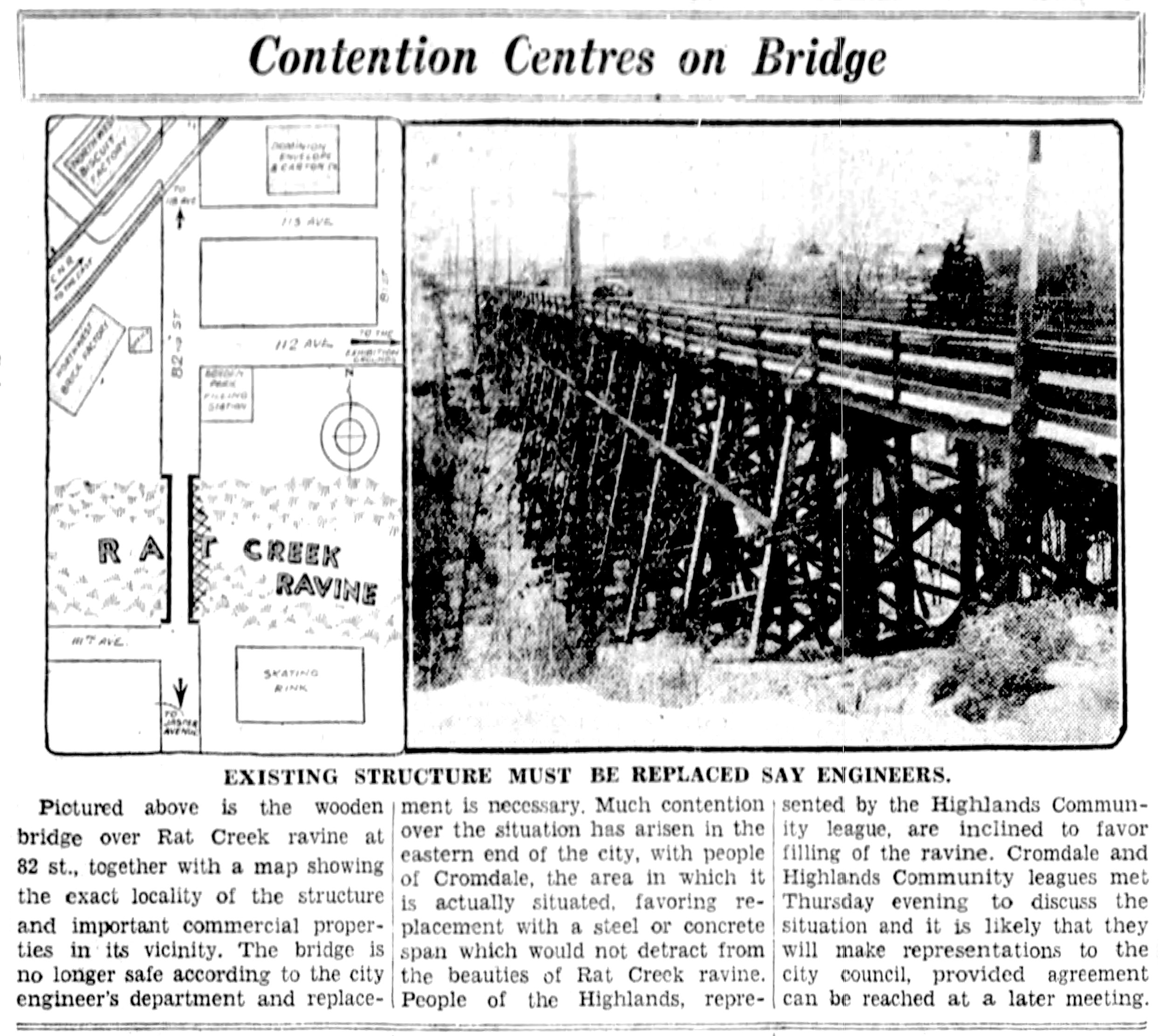

The old Kinnaird Ravine trestle had seen better days. It was a simple timber bridge, erected in 1909 at a cost of $7,000. City officials always maintained that it was a stopgap until something bigger and better could come along — two decades later and nothing had. By January 1931, with inspectors and citizens alike worried that it was on the verge of collapse, City Council ordered a replacement.

Details over how to proceed held back work significantly. Structural design, and the choice of concrete versus steel construction in particular, was one major hurdle. City engineers suggested steel, “preferring it because of its greater flexibility owing to the street railway traffic which the structure must carry. On the other hand, a concrete bridge would cost slightly less, would be almost wholly of Alberta material, and would be much more attractive.” The Left-wing Edmonton Trades & Labour Council, representing many of Edmonton’s unionized workers, preferred the concrete option “which [gave] the greatest amount of labour” potential.

Filling-in Kinnaird Ravine was another consideration. Although touted as a large-scale Great Depression make-work project, where “employment would be given [to] 100 men for several weeks,” community buy-in was minimal. One delegation from the Cromdale Community League disagreed, citing a fill as preferential owing to “disrupted traffic to Cromdale and the Highlands that would be necessary if the bridge was built,” but a subsequent meeting of community members in early December “left no room for doubt” that the neighbourhood overwhelmingly supported either a steel or concrete bridge above the ravine.

The timing of their consensus was fortunate. For months, officials had been warning that the Kinnaird trestle’s worsening state made it “no longer safe.” Ad-hoc repairs were all that kept it from complete condemnation, and the November prior the old bridge, rickety as it was, nearly killed three people. As the Edmonton Bulletin explained:

“Wildly skidding 48 feet across the intersection of 111 avenue and 82 street at 1:50 a.m., Sunday, [November 23rd, 1931,] a Chevrolet coupe driven by Alex Hamilton of Armena, Alberta, crashed through the heaving railing at the side of the 82 street bridge, plunged backward, and dropped 50 feet to the bottom of the Rat Creek Ravine. Hamilton suffered cuts to his right arm. Robert Jacobs of 5001 110 avenue, a passenger, escaped injury, while Clara Macks of 11926 95A street sustained severe cuts and lacerations to her right ankle.”

Ultimately, the City went with a conservative steel-construction bridge, featuring concrete deck and inlaid streetcar tracks. As part of Edmonton’s Depression relief programme, the Dominion Bridge Company was awarded tender on the condition that “the utilization of unskilled unemployed labour,” paid fair union rates, comprised most of its projected four-to-five hundred man crew. Unionized steelworkers were to oversee the City’s relief workers.

Projects like Edmonton’s Kinnaird Bridge were tenuously funded through the federal government’s ad-hoc Unemployment Relief Act and subsequent Unemployment and Farm Relief Act. Begrudgingly introduced by Prime Minister Richard B. Bennett’s Conservative government in 1930 and 1931 respectively, the two pieces of legislation hoped to function as some form of Depression relief. The Unemployment Relief Act specifically allocated $20,000,000 in assistance for the unemployed, a sum “then considered enormous because it was ten times the amount spent for the entire decade of the twenties [on unemployment relief].” Four-fifths of that money would cover up to twenty-five percent of any make-work project’s cost, to be given out to any municipality that could prove it had a project that could create jobs.

Although the municipal assistance seemed a benevolent gift handed down by the charitable hand of the Dominion, Canada’s archaic constitution made it anything but. As Eric Strikwerda explains in Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929-39:

“It was under the legislative authority of these two acts that most of the urban work relief projects in the early 1930s took place. But the legislative framework, despite the hope it offered, was unwieldy, requiring municipal authorities to submit relief work proposals to their respective provincial governments for approval rather than to the federal government directly. The provinces would then resubmit those proposals to Ottawa, and federal funding for approved projects would finally flow back to the cities through the provincial governments.”

Pierre Burton writes that this system “divided responsibility in such a way that the destitute could not rely on help from anyone.” Bennett, the abrasive self-made millionaire and staunch Edwardian moralist, was largely uninterested in the poor’s plight. Standing on the rock of the British North America Act, the Prime Minister washed his hands of the matter. He delivered a campaign promise, and that’s all that mattered, no matter how broken the apparatus of deliverance was.

Still, for a municipality like Edmonton — one of Canada’s poorest — it was better than nothing. The Dominion shouldered much of the Kinnaird Bridge’s projected $71,900 cost through both the Unemployment and Farm Relief Act and subsequent grants. In all, Edmonton taxpayers spent only $27,500.

Work began in earnest on December 29th, 1931 with foundation boring. The completion of new concrete footings by January 19th then permitted the removal of the old wood trestle. “Construction of [this] new bridge has progressed to such a point that dismantling of the old bridge is essential, [A.W. Haddow, City Engineer] said.” However, “unforeseen delays” pushed this from the 22nd to the 25th, and further disruptions continued well into April.

This posed a problem for the city’s rail-bound streetcar network. While new rails were to be installed on the old bridge’s replacement, in the interim traffic needed to be diverted. For instance, cars running to the Highlands — which once traveled east along Jasper Avenue, north up 82nd Street, and east down 112th Avenue — were forced to instead divert “via 101st Street [to] 111th Avenue, 114th Avenue (Spruce Avenue), and the Exhibition Grounds spur to the Highlands.” W.J. Cunningham, Power & Street Railway Superintendent, attempted to assuage fears stating that the new “jog” was only “but a few minutes extra.” Although the Edmonton Radial Railway maintained fifteen minute headways, the far greater geographical area covered made trips less direct and longer as a result, despite Cunningham’s statement to the contrary.

Transit riders complained, and they weren’t alone. The Journal reported that “A.E. Kinnear, who operates a filling station at 112 ave. and 82 st., will ask that the city rebate his 1932 license fee of $75. He declares that he has lost considerable business through the re-routing of traffic as a result of the Rat Creek ravine bridge construction and the closing of 82 st.”

But those who truly struggled were the one’s building the bridge. The City’s relief workers risked life and limb in treacherous conditions, withstanding “sub-zero temperatures and the freezing blasts of a prolonged cold spell.” As the Journal wrote:

“Perched on swaying girders in the face of biting winds the hardy bridge-workers have carried on with their job. But the men responsible for the excavation work have found it a much harder task. Deep-frozen ground, tangled underbrush and poor working conditions have combined in an effort to hold up the work.”

Cheated out of reasonable pay were five workers. At the City Finance Committee’s May 9th meeting Mayor Daniel K. Knott candidly revealed “that union men [working on the bridge] had received $1 per hour, while non-union members received between 70 and 90 cents per hour.” Alderman James W. Findlay was disgusted by the news. Edmontonians elected the creased brow, steely-eyed friend of the working class on a socialist platform the previous November. The one-time Edmonton Trade & Labour Council member got up and vigorously “protested that five steel workers were paid below the union fair wage rate… He said that money should be retained by the city, from the sum due to the contractors, and paid to the men.” More timid members of Council refused to debate the matter and “no action was decided upon.” Nevertheless, Findlay pushed and city commissioners agreed to investigate the wages paid out by the Dominion Bridge Co. Their motive came to the attention of aldermen on July 15th. As the Council’s minutes read:

“Messers. McIntosh and Whyte, representing certain Iron Workers and Local No.126 who were employed on the 82nd. Street bridge by the Dominion Bridge Company, appeared claiming that they are entitled to additional wages.”

The two argued that the Company considered them only “helpers” and not certified journeymen. “His worship advised them to produce proof they were journey men [sic],” the Journal explained, but until the dispute was settled, he agreed they would withhold the promised payment.

While reliefers struggled to secure their hard-earned cash, municipal spokesmen were citing the bridge as a hallmark of the City’s successful $850,000 unemployment relief program. They even used the bridge’s cost overruns — its total ballooned to $82,000 on account of using unemployed labour, or so officials claimed — as a testament to the City’s attempts to halt the worst of the Depression’s effects. Perhaps it was theatrics to distract from an unsightly story or perhaps it was simple boosterism. Whatever the intended message, the ongoing struggle over underpaid labour was largely ignored by the press and Edmontonians at large.

The new Kinnaird Ravine Bridge officially opened at 5:00 p.m. on Saturday, April 30th, 1932, just in time for an Edmonton Grads game over at the Arena. Streetcar services returned to 82nd Street the following day. By Sunday’s end, estimates suggested over 10,000 Edmontonians tried out the crossing.

For his part, Alderman Findlay kept on the workers’ case, even if it faded from the public eye. Months passed, and by the time it came back to Council on February 13th, 1933, nothing had yet been achieved. “Negotiations between the city, Dominion Bridge Company, and five men who are protesting… have reached deadlock stage,” the Bulletin lamented, “and city commissions are recommending that further negotiations be discontinued.” His Worship and the reliefers agreed. As the minutes read:

“Mayor Knott verbally reported that Mr. F.B. Pennock acting for the employees has requested that this [matter] be laid over for the purpose of allowing interested parties to make a settlement.”

Findlay begrudgingly moved the motion. Whether the labourers got their due or not has been lost to history.

Image Gallery:

Sources:

“New Bridge Finished,” Edmonton Bulletin, October 19, 1909.

“Jobs Galore If Funds Found; City Strives to ‘Make’ Work,” Edmonton Journal, May 28, 1931.

“Labor Will Sponsor Seven Candidates For Civic Office,” Edmonton Journal, September 30, 1931.

“Council Approves Plans for Bridge Rat Creek Ravine,” Edmonton Journal, October 27, 1931.

“Who’s Who Among Men Elected to Civic Post,” Edmonton Journal, November 12, 1931.

“Auto Skids Off Bridge; Two Injured,” Edmonton Bulletin, November 23, 1931.

“Work Delayed On New Bridge For Two Weeks,” Edmonton Journal, November 24, 1931.

“Contention Centres on Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, December 1, 1931.

“Cromdale Community Opposes Rat Creek ‘Fill-in’,” Edmonton Journal, December 2, 1931.

“Bridge Is Favored,” Edmonton Journal, December 3, 1931.

“Labor Men Favor Concrete Bridge Over Rat Creek,” Edmonton Journal, December 8, 1931.

“Commence Work On New Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, December 29, 1931.

“Pouring Footings For New Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, January 19th, 1932.

“Passenger Bus Starts Running Monday Morning,” Edmonton Journal, January 22, 1932.

“No Disruption Usual Service Highlands Car,” Edmonton Journal, January 26, 1932.

“Rat Creek Bridge Rushed Forward,” Edmonton Journal, February 25, 1932.

“14 Exceptions From Closing Law Being Proposed,” Edmonton Journal, March 14, 1932.

“Double Shifts Work On Bridge,” Edmonton Journal, March 16, 1932.

“Will Open Bridge Early To Assist Traffic Basketball Game,” Edmonton Journal, April 30, 1932.

“What Council Did,” Edmonton Bulletin, May 10, 1932.

“Firm’s Proposal To Assist City Will Be Study,” Edmonton Journal, May 10, 1932.

“New Bridge in West End One of Finest in Canada,” Edmonton Journal, June 29, 1932.

“Opening Hearing of Wage War,” Edmonton Bulletin, July 22, 1932.

“Steel Workers’ Dispute Reaches Deadlock Stage,” Edmonton Bulletin, February 13, 1933.

“Fair Wage Scale — 82nd. Street Bridge,” Meeting No.31, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, July 15, 1932, 1, City of Edmonton Archives,

“Wage Dispute 82nd. St., Bridge,” Meeting No.3, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, December 12, 1932, 14, City of Edmonton Archives,

“82nd. Street Bridge — Wage Dispute,” Meeting No.8, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, February 13th, 1933, 8, City of Edmonton Archives,

“Bridge — 82nd. St (Wage Dispute.),” Meeting No.9, Edmonton City Council Meeting Minutes, February 27th, 1933, 8, City of Edmonton Archives,

Pierre Burton, The Great Depression: 1929-1939 (Toronto; Penguin Books, 1990), 38, 76, 77.

Eric Strikwerda, Wages of Relief: Cities and the Unemployed in Prairie Canada, 1929-39 (Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2013), 102.